Rethinking the Familiar

When the Candle Works Too Well

For most of human history, night was not just a time of day. It was a boundary; a limitation.

When the sun went down, commerce slowed, travel tightened, and households compressed into the radius of whatever light they could reliably produce. A community’s “after hours” depended less on ambition and more on the physics of flame. You planned dinner, reading, repairs, even conversation around the same practical question: how long will the light last, and how much will it cost to keep it?

For centuries, the candle was the answer. Not a perfect answer, but a dependable one. People refined it the way humans refine anything that proves useful. Better wax. Better wicks. Cleaner burns. Lanterns that protected the flame from wind. A small technology, iterated into a system, then woven into habit until it felt like permanence.

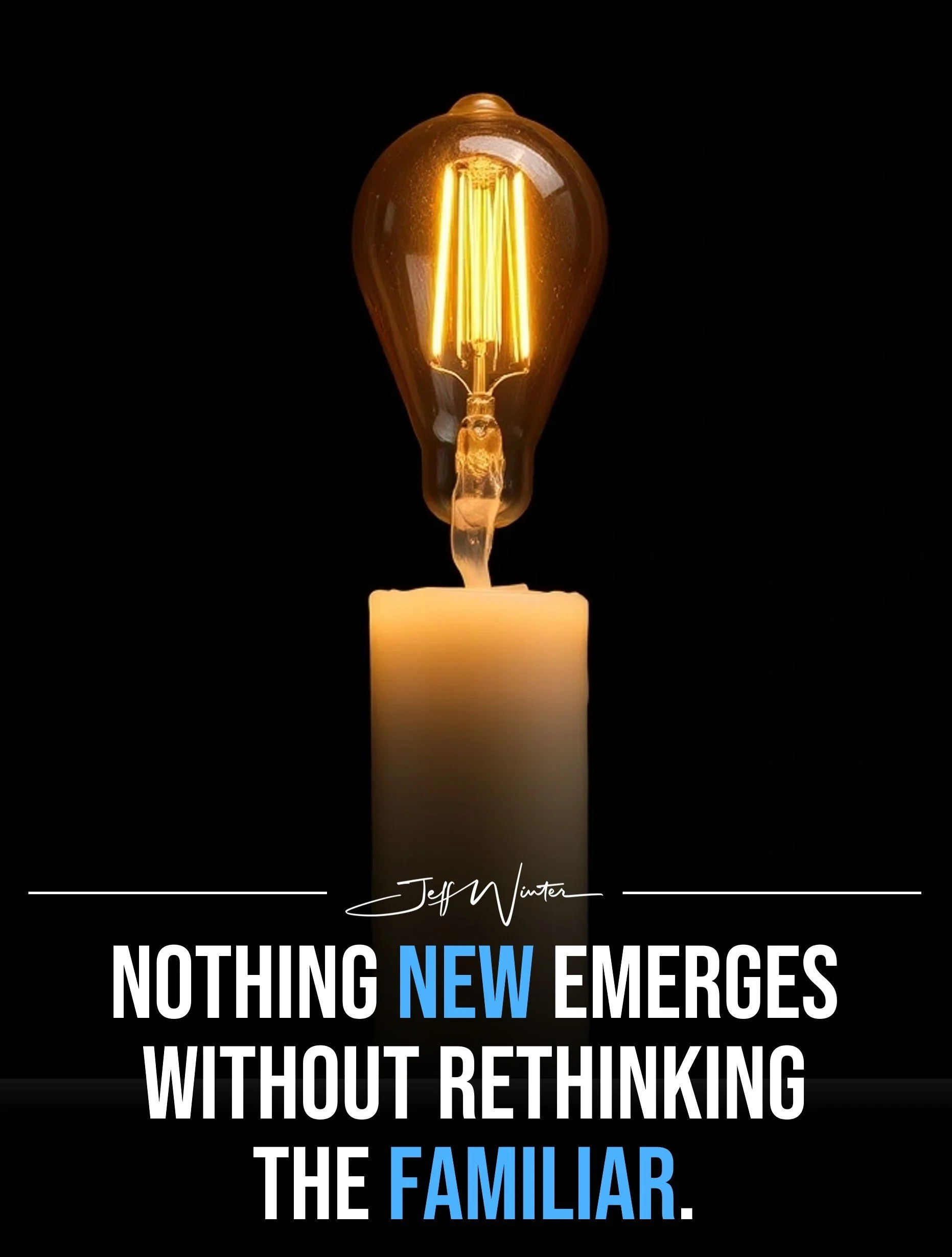

It worked. It gave light. It was reliable. And reliability can be its own kind of trap, because it encourages a subtle confusion: we start to believe the tool and the outcome are the same thing. We stop thinking “light,” and begin thinking “candle,” as if illumination can only arrive in the shape we already recognize.

Then someone did the inconvenient thing. They reconsidered the familiar. Not “How do we make a brighter candle?” but “What if light did not require a flame at all?” That pivot is where the future usually starts. “Nothing new emerges without rethinking the familiar” is not a poetic suggestion. It is a pattern you can spot in every real shift, from the light bulb to the refrigerator to the smartphone. The breakthrough is rarely a louder version of the old solution. It is a different definition of the problem.

The Candle Problem Shows Up Everywhere

We live in a world that praises innovation, yet most of us spend our days upgrading candles. A company improves a process without revisiting the assumptions that created it. A team adds a tool without changing the decision rights that slow work down. An industry pushes efficiency while leaving its definition of value untouched. The result looks productive and feels stagnant, because motion is not the same as emergence.

This is why the candle is such a useful metaphor. It is not that the candle is foolish. The candle is rational. It is the best answer inside a certain frame. The issue begins when the frame becomes invisible. That is also why the “faster horses” story still circulates. The line is often attributed to Henry Ford, though there is dispute about whether he actually said it, and even Ford-linked voices have clarified that it is not an authentic Ford quote. The deeper point, however, survives the attribution debate: customers frequently describe improvements to the tool they know, not a reinvention of the job they are trying to get done.

If you asked people for a better candle, many would have asked for a candle that burned longer, smoked less, and did not drip on the table. All reasonable. None of them require electricity. This is where rethinking the familiar stops being a slogan and becomes a discipline. You have to separate the need from the method. You have to learn to hear “I want to get there faster” instead of “I want a faster horse.” You have to train yourself to notice when an organization is equating “better candles” with “more light.”

The Innovation Climate Has Been Nudging Us Toward Candles

In the last year, the data has offered a quiet warning: the global system is not short on ideas, but it is showing signs of leaning toward caution, concentration, and incrementalism. One signal is investment in the raw material of invention. WIPO’s Global Innovation Index 2025 tracker reports that global R&D growth slowed to 2.9% in 2024 and is projected to fall further to 2.3% in 2025, which WIPO frames as the weakest expansion in over a decade.

A second signal is how the market is funding experimentation. The same WIPO tracker notes that in 2024, venture capital deal values rose 7.7%, yet the number of VC deals fell 4.4%. That combination is telling: capital can rebound while experimentation still narrows, with fewer bets receiving more money.

A third signal is internal, and it should feel familiar to anyone who has sat through an “innovation initiative” that never touched the operating model. PwC’s 29th Global CEO Survey reports that only 8% of CEOs say their company has implemented at least five of six “innovation-friendly practices” to a large or very large extent.

These statistics do not say the world has stopped innovating. They suggest something more subtle and arguably more dangerous: we are optimizing within familiar frames at the exact moment when the environment is demanding reframing. We are getting better at candle-making while the room we are trying to light is changing shape.

What Rethinking the Familiar Actually Looks Like

Rethinking is not rebellion for its own sake. It is not contrarianism. It is the willingness to treat yesterday’s defaults as drafts. That sounds abstract until you see it in other transitions. Iceboxes and daily ice deliveries were a functioning system until refrigeration reframed the problem. Paper maps were effective until GPS turned navigation into a dynamic, real-time service. Film cameras were a craft until digital imaging collapsed the cost of experimentation and put photography into the flow of daily life.

In each case, the “new” did not arrive because someone was obsessed with novelty. It arrived because someone questioned what everyone else had stopped questioning. They asked what the candle was doing, not how to polish it. This is also why many smart organizations struggle. The familiar has social power. It is attached to expertise, status, budgets, and identity. Changing it can feel like criticizing the people who built it. And so, rather than confront the frame, we decorate it. We add dashboards. We rename departments. We run pilots designed to validate what leadership already believes. We hold workshops that generate sticky notes but never touch incentives.

So what does a more serious approach look like, especially for leaders who need results, not slogans? Here is a single field guide you can actually use, whether you are building a product, redesigning a function, or trying to unstick a strategy.

A simple field guide for blowing out the candle

State the outcome without the tool. Write the goal as a human need, not as an inherited method. You do not need “a new approval workflow.” You need “faster decisions with the right risk controls.”

Name the hidden assumption. If a team keeps struggling, ask what they believe must be true. “Customers will not self-serve,” “quality requires manual review,” “sales must be human-led,” “compliance means saying no.”

Attack one assumption with a small, sharp experiment. The point is not to prove you are right. The point is to learn faster than your current certainty.

Change the measurement before you change the behavior. If you reward utilization, you will get busyness. If you reward learning speed, you will get experimentation. If you reward certainty, you will get politics.

Retire something on purpose. Make space by removing a step, a report, a meeting, a policy, or a product feature. If nothing ever gets turned off, you are not innovating. You are accumulating.

The Candle Is Not the Enemy, but It Cannot Be the Ceiling

The candle remains useful. It is portable, simple, and resilient. In a power outage, it becomes valuable again. That is the point: familiarity is not inherently bad. It is just rarely the birthplace of something new unless we are willing to look at it differently.

The quote holds because it describes how emergence actually happens. Nothing new emerges without rethinking the familiar because the familiar is the container. It defines what questions are allowed, what trade-offs are assumed, what risks are tolerated, and what “good” looks like. When the container goes unquestioned, novelty can only be cosmetic.

A better candle will always be appealing. It will always feel practical. It will always sound responsible in a meeting. But if what you really need is light, sooner or later you have to challenge the assumption that flame is the only way to get it.

References:

World Intellectual Property Organization. (2024). Global Innovation Index 2025: Global Innovation Tracker. https://www.wipo.int/web-publications/global-innovation-index-2025/en/global-innovation-tracker.html

WPC (2026). 29th Global CEO Survey: Leading through uncertainty in the age of AI (PDF). https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/ceo-survey/2026/pwc-ceo-survey-2026.pdf