Humanoid Robots are Closer Than We Think

The hardest problem in humanoid robotics is no longer intelligence.

For decades, that was our psychological safety blanket. Robots could move. Robots could lift. Robots could repeat. But they could not reason, adapt, or understand the world the way humans do. That belief allowed us to keep humanoid robots safely parked in the future. That belief is now wrong.

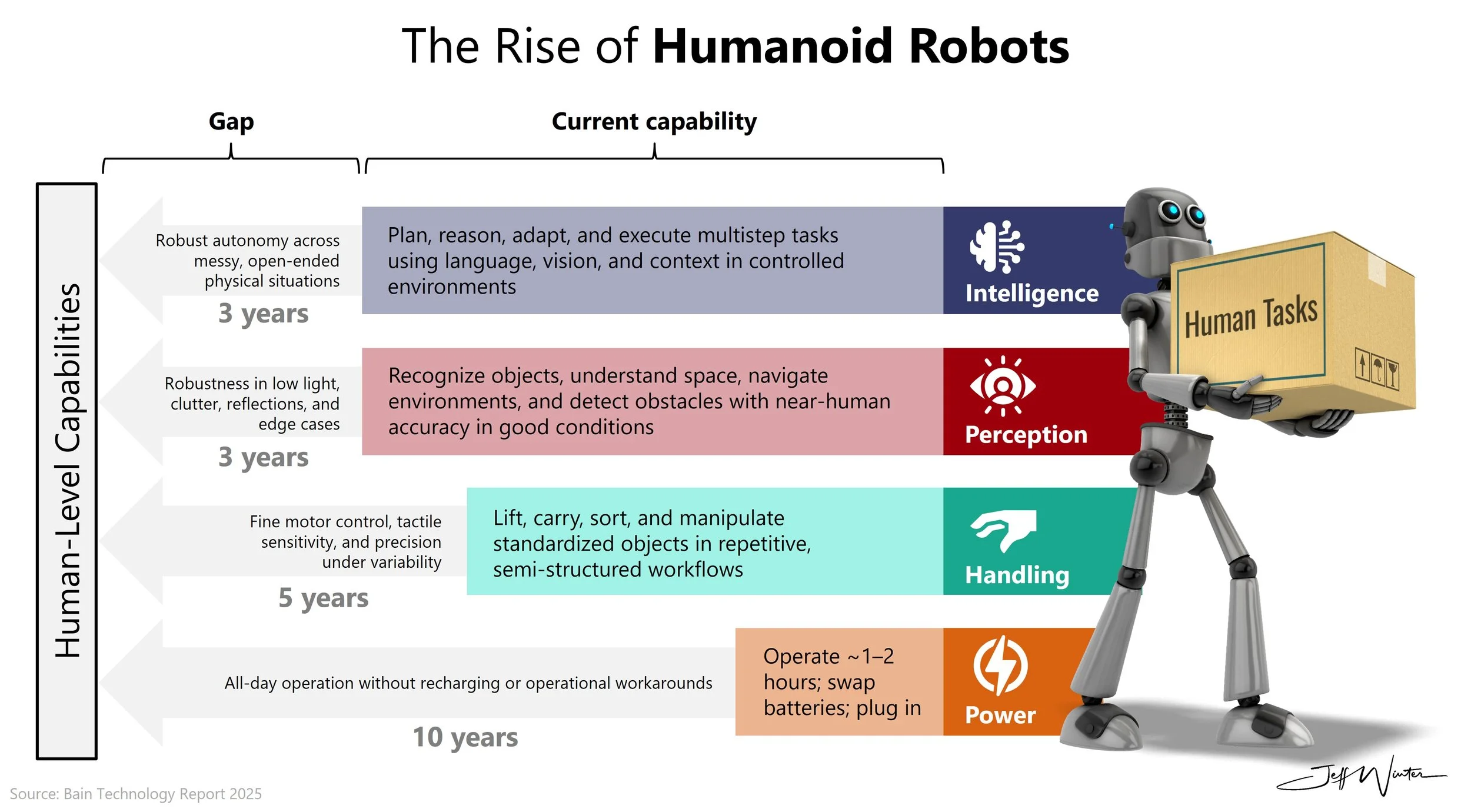

According to Bain’s Technology Report 2025, intelligence and perception are the two humanoid capabilities advancing the fastest, and both are approaching human-level performance far sooner than most public conversations suggest. Bain estimates that within roughly two to three years, robots will match humans in core reasoning, planning, and perception tasks in structured environments.

The Part Everyone Gets Backwards

Most discussions about humanoid robots focus on what they still cannot do. Fine motor control. Battery life. Delicate manipulation. All of that is true. But it misses the strategic point.

Humanoid robots do not need to replicate everything a human can do to be disruptive. They only need to outperform humans in the specific places where economics already hurt. Bain frames humanoid capability across four dimensions:

Intelligence

Perception,

Handling

Power.

Two of those are racing ahead. Two are lagging. And that imbalance is exactly why humanoids will arrive sooner than expected, not later.

The Brain Problem Is Mostly Solved

On intelligence, modern humanoid robots can reason through multi-step tasks, plan sequences of actions, adapt when conditions change, and integrate language, vision, and spatial context into a single decision loop. Generative and agentic AI allow robots to understand goals rather than follow rigid scripts. In many constrained physical tasks, this level of intelligence is approaching or exceeding average human performance.

Perception is close behind. Advanced vision systems now allow robots to recognize objects, navigate space, track motion, and understand their environment with near-human accuracy in good conditions. Bain again places perception within roughly three years of human-level capability, with remaining gaps tied mostly to edge cases rather than core function.

We (or at least I) assumed robots would get bodies before they got brains. Instead, we gave them cognition first.

The Body Is Still Catching Up

Handling and power remain real constraints. Dexterity and tactile sensitivity still lag human capability. Robots can lift, carry, sort, palletize, and handle standardized objects reliably, but struggle with fine motor control and delicate manipulation. Precision manufacturing and lab environments remain harder to automate without cost escalation. Battery life is the longest pole. Most humanoids today operate for one to two hours. Bain estimates that true eight-hour, untethered operation could take up to a decade without major energy density breakthroughs. Near-term deployments will rely on battery swapping, fast charging, or tethered power.

The most important part to know thought is that none of those limitations stop deployment in the places that matter most. This is where many people incorrectly conclude that humanoids are still far away. That conclusion misses the economic point.

Humanoids Do Not Need to Be Fully Human

Humanoid robots do not need to match human capability across all dimensions to be disruptive. They only need to be good enough in the right places. Early deployments will not happen in homes or cities. They will happen in highly structured environments where layouts are known, workflows are repeatable, and variability is limited. Factories. Warehouses. Logistics hubs. Hospitals. Hotels. Transportation yards.

These environments already optimize for consistency. They already constrain human behavior through processes, safety rules, and standardized work. In those settings, the remaining gaps in dexterity and battery life are manageable operational problems, not existential barriers.

My opinion is simple: this is why the first wave will feel boring.

No humanoid robot moment. No sudden takeover. Just one aisle automated. One night shift covered. One hospital supply run replaced. One logistics bottleneck removed. Then another.

The Real Disruption Is Not Jobs, It Is Assumptions

Bain frames humanoids as part of a broader automation toolkit responding to demographic decline, labor shortages, and productivity pressure. In advanced economies, working-age populations are shrinking by as much as 25% in some regions. That pressure is structural, not cyclical.

This is where I will go further than the report. Humanoid robots are not coming for jobs in the abstract. They are coming for three assumptions we still hold:

First, the assumption that labor shortages are temporary. They are not. Demographics do not reverse quickly.

Second, the assumption that productivity gains must come from humans working harder or longer. Once intelligence becomes software, that assumption collapses.

Third, the assumption that physical work cannot scale the way digital work does. Once cognition is decoupled from biology, physical labor becomes an optimization problem.

And optimization problems always get solved.

What I Expect to See Next

Based on Bain’s timelines and what we see in adjacent automation markets, here is what I expect over the next five years. We will see humanoids deployed first as task specialists, not general workers. Tote handling, palletizing, line feeding, hospital logistics, hotel room reset, hazardous material handling. Narrow scope. High repetition. Clear ROI.

We will see hybrid designs win early. Wheeled bases with humanoid torsos. Limited dexterity paired with strong perception. Less emphasis on walking, more emphasis on useful work. We will see “human-in-the-loop” persist longer than people expect. Not because robots cannot think, but because safety, regulation, and trust lag capability.

And we will see organizations that redesign workflows early capture disproportionate advantage. Bain is explicit that early pilots, infrastructure investment, and workforce trust building will separate leaders from laggards.

The real question is whether organizations will decide deliberately where humans add the most value, or whether that decision will be made for them by economics and vendors.

References:

Bain & Company. (2025). Technology Report 2025. Retrieved January 10, 2026, from https://www.bain.com/insights/topics/technology-report/