Maslow Goes to the Factory: The Hierarchy of Manufacturing Needs

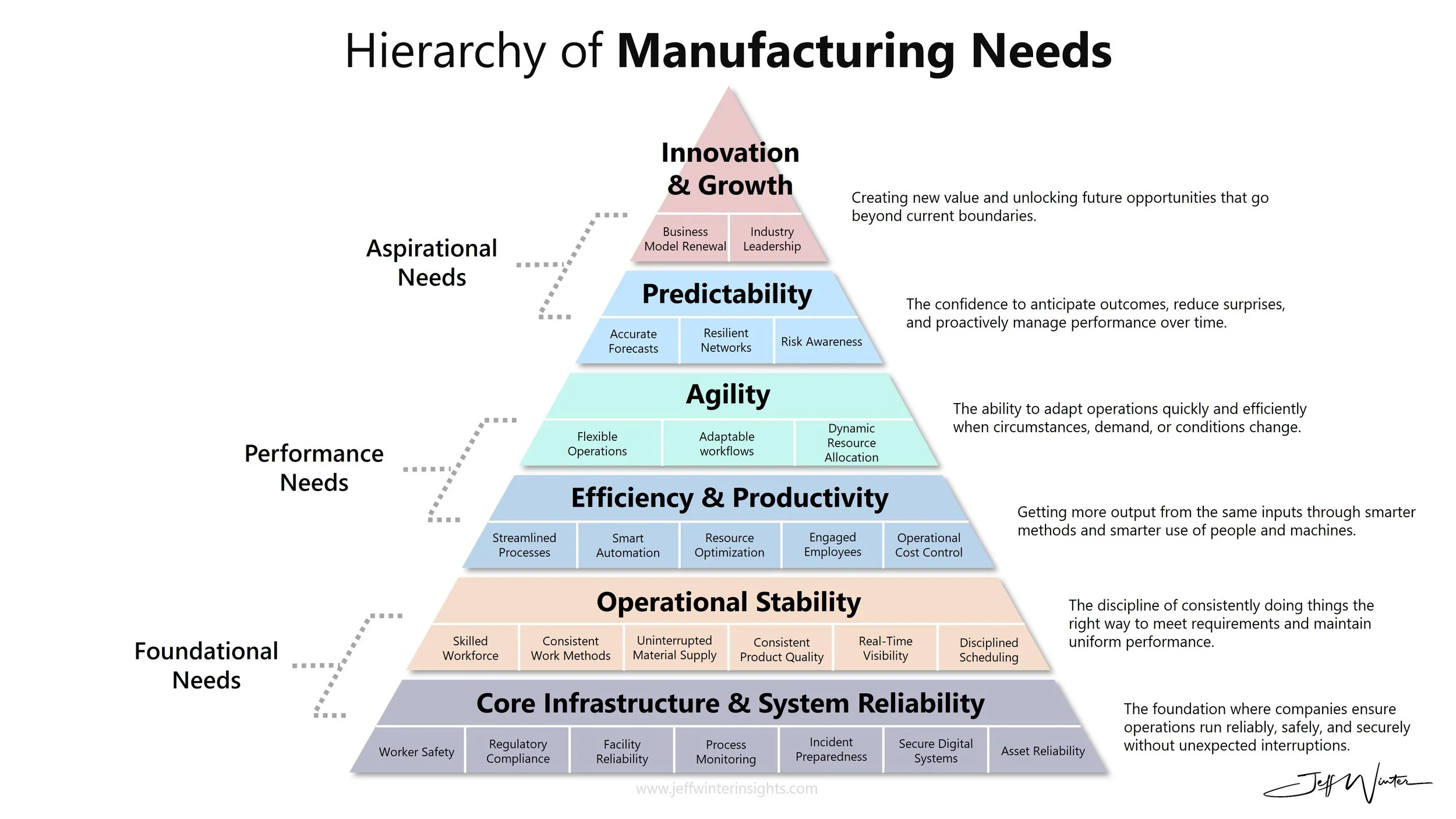

Abraham Maslow probably never imagined his Hierarchy of Needs would one day be hijacked for the world of shop floors and supply chains. But here we are. Of course, this is a spoof. I am taking one of the most famous theories in psychology and giving it a manufacturing makeover, partly for fun, partly because the parallels are actually too good to ignore. Maslow mapped out human motivation, showing that people climb from physiological basics (food, water, shelter) up to lofty ideals like love, esteem, and finally self-actualization. Factories don’t need hugs or self-esteem, but they do have their own pyramid of priorities, a Hierarchy of Manufacturing Needs, and the structure looks suspiciously familiar once you sketch it out.

Of course, there are important differences. We’ve borrowed a famous psychological theory and given it a hardhat makeover. The parallels are surprisingly strong, but the differences matter too. People can skip a meal and still muddle through; factories skipping maintenance or safety won’t last long. Humans need connection to feel whole; factories need stable supply chains and consistent processes. And while self-actualization for a person might mean writing a novel, for a manufacturer it’s redefining markets through innovation.

I spoofed Maslow’s pyramid into a Hierarchy of Manufacturing Needs to make a point. It’s not meant to be perfect or exhaustive, manufacturing is too complex for that. Anyone who’s spent time on a shop floor knows there are a hundred other factors that matter, and probably a few more layers we could add if we wanted to get granular. The goal here isn’t to capture everything, it’s to capture the essentials that apply to the broadest number of manufacturers.

The power of using Maslow’s frame is in its simplicity. Everyone instantly understands the logic: you can’t skip the basics and expect to thrive at the top. The same holds for factories. You can’t ignore safety, reliability, or stability and still expect innovation to stick. The pyramid is just a metaphor, but it works because it forces leaders to ask themselves: Which level are we really standing on? And are we ready for the next climb?

So no, this pyramid doesn’t cover every nuance of your operation. It’s not a checklist or a substitute for strategy. It’s a mirror. And mirrors, by design, are blunt. They don’t tell you everything, but they show you enough to know whether you’re ready to move up.

Foundational Needs: Building the Bedrock

Every great factory needs a rock-solid ground floor. Foundational Needs are the must-haves that keep the lights on and the machines running. They’re the equivalent of a factory’s physiological and safety needs, the bedrock of reliable production. No fancy AI or cutting-edge innovation will save you if your basic infrastructure is crumbling. As one saying goes, “You can’t build a great house on a shaky foundation.” In manufacturing terms: if your equipment is catching fire (literally or figuratively), you’re not going to worry about launching a new product line next week.

Foundational Needs encompass two major categories: Core Infrastructure & System Reliability and Operational Stability. Let’s unpack each and the critical subcomponents that make them up:

Core Infrastructure & System Reliability

This is the ground floor of the entire pyramid, the core systems, assets, and practices that keep the factory operating safely and predictably day in and day out. It’s all about ensuring operations run without unexpected interruptions. Here are the key pieces of Core Infrastructure & Reliability, explained in plain language:

Worker Safety: Nothing is more important. Every employee should go home in one piece, every day. This means protective equipment, safety protocols, and a culture that puts people first. If you think safety is expensive, try an accident.

Regulatory Compliance: Following the rules and laws that govern your operations, from OSHA safety regulations to environmental standards. It’s the “eat your vegetables” of manufacturing needs: not exciting, but neglect it and you’ll face hefty fines or shutdowns. Compliance keeps your license to operate.

Facility Reliability: Keeping the power on, the roof intact, and the production line utilities (water, air, energy) reliable. A well-maintained facility avoids leaks, power failures, and other gremlins that can halt production. It’s ensuring your physical plant isn’t the weak link.

Process Monitoring: You can’t improve (or fix) what you don’t measure. Having sensors, gauges, and data tracking on your processes means you get early warning of problems and can continually improve. Real-time monitoring of temperature, pressure, speed, etc., helps catch issues before they balloon.

Incident Preparedness: Even with safety and maintenance, stuff happens; a fire, a flood, a system crash, etc.. Incident preparedness means having fire drills, backups, spare parts, and emergency response plans ready. It’s the factory’s version of a first aid kit and insurance policy. When you’re prepared, an unexpected event might be a small blip rather than a catastrophic shutdown.

Secure Digital Systems: Modern factories run on software and networks as much as on gears and grease. Cybersecurity for operational technology (OT) systems, data backups, and network reliability are crucial. A virus in your production network can stop a line just as surely as a broken machine. In an era of ransomware and cyber-attacks, digital reliability is plant reliability.

Asset Reliability: Keep machines and equipment in good health. Through preventive maintenance, predictive analytics, and good old daily care, asset reliability means each machine does what it’s supposed to, when it’s supposed to. No one likes that one temperamental machine that’s always breaking down at the worst time. Reliable assets = higher uptime.

Operational Stability

If Core Infrastructure is about machines and systems, Operational Stability is about the human and process side of running a tight ship. It’s the discipline of doing things consistently “the right way” to meet quality and schedule every day. Think of Operational Stability as the factory’s daily rhythm and reliability, the reduction of variability and chaos in operations. As one might say, “Smooth is fast.” When everything runs smoothly and predictably, you hit your targets and can start improving. Here are the elements that make up Operational Stability:

Skilled Workforce: People are the heart of manufacturing, but not in the “train them to push the same button forever” sense. A modern workforce must stay current on technology and continuously build new skills, from data literacy to AI. It’s not enough to create repetitive robots in human form; the real advantage comes when employees contribute to company strategy, applying their knowledge to solve problems, spark innovation, and improve how things get done. For example, a technician who understands how to use AI-driven analytics isn’t just running a process, they’re shaping better decisions and finding opportunities others miss. A truly skilled workforce doesn’t just operate the system, it evolves the system.

Consistent Work Methods: Standard operating procedures (SOPs), best practices, and a culture of doing tasks the right way every time. This is the Toyota secret sauce. They document the best way to perform each task and train everyone to do it that way for consistency and quality. When every shift and every site does a process the same proven way, you don’t get random quality problems or efficiency slumps. Consistency is the mother of reliability.

Uninterrupted Material Supply: Even a world-class factory can’t run if it runs out of parts or materials. Stable operations require good supply chain management and inventory strategies so that materials arrive just in time, but not late. (We all saw what happens when supply chains break: e.g., the 2021 chip shortage that forced many automakers to halt production.) This sub-need is about having the right raw materials at the right place, all the time. Dual sourcing, safety stock, and good supplier relationships are typical strategies to ensure material flow never stops.

Consistent Product Quality: Quality at the source, making each product right the first time, every time. This covers robust process control, quality checks, and a culture of stopping production if a serious defect is detected (rather than shipping bad product). The goal is to never surprise the customer with a faulty product. For example, Toyota’s legendary quality didn’t happen by accident, it comes from consistent methods and empowering workers to pull the Andon cord to fix issues immediately, thereby preventing defects from snowballing. High quality not only keeps customers happy but also avoids costly recalls and rework.

Real-Time Visibility: Knowing what’s happening on the factory floor as it happens. This might be production dashboards, IIoT sensors streaming data, or managers doing frequent gemba walks. Real-time visibility is the antidote to the “fog of war” in operations, it lets you respond to small problems before they become big ones.

Disciplined Scheduling: A disciplined schedule factors in realistic production rates, maintenance windows, and buffers for the unexpected. When schedules are stable and sane, workers aren’t constantly firefighting or forced into overtime, and customers get their deliveries on time. As the saying goes, “Failing to plan is planning to fail.” Disciplined scheduling helps avoid that failure.

Performance Needs: Accelerate and Excel

With a solid foundation in place, a manufacturer can shift focus from surviving to thriving. Performance Needs are the middle layers of the pyramid, where the organization moves from stability to efficiency, agility, and predictability. In Maslow terms, if foundational needs were like physiological/safety, these are akin to belonging and esteem needs, the factory is now humming well, and wants to optimize and excel. This is about doing things better, faster, and smarter.

Performance Needs are grouped into three major categories: Efficiency & Productivity, Agility, and Predictability. Mastering these gives a company a competitive edge, more output for less input, quicker responses to change, and fewer surprises along the way. Let’s break down each:

Efficiency & Productivity

This category is all about the classic mandate: work smarter, not harder. Efficiency & Productivity means getting more output from the same resources, eliminating waste, and continuously improving throughput. It’s the realm of lean manufacturing, automation, and employee engagement, all geared toward doing more with less (or at least more with the same). Key subcomponents here include:

Streamlined Processes: Simplifying and optimizing workflows to remove non-value-added steps (aka waste). This is Lean 101: cut out the unnecessary movements, overprocessing, waiting time, etc. A streamlined process is like a well-oiled assembly line with no bottlenecks or detours.

Smart Automation: Using technology and machines to automate repetitive, dangerous, or precise tasks. Robotics, AI, and advanced machinery can greatly boost productivity and consistency. Smart automation isn’t about replacing people so much as augmenting them, letting machines do the heavy lifting or monotonous work so humans can focus on tasks that need judgment. Done right, automation raises throughput and quality simultaneously.

Resource Optimization: Using resources (materials, energy, labor) as efficiently as possible. This could mean better production planning to maximize equipment utilization, reducing scrap material through better nesting in cutting operations, or saving energy via smarter HVAC and machine idle settings. Optimized resource use goes straight to the bottom line as cost savings. And as a bonus, it often helps sustainability by reducing energy and material waste.

Engaged Employees: People who are motivated, involved, and empowered to improve things. It might surprise some, but employee engagement is a huge factor in productivity. Engaged workers tend to come up with improvement ideas, need less supervision, and generally work more effectively. Conversely, a disengaged workforce will just “punch the clock” and not go the extra mile, which is a huge lost opportunity.

Operational Cost Control: Keeping a tight handle on the costs of production. This involves budgeting, monitoring cost drivers, and relentlessly improving processes to cut cost per unit. It could mean negotiating better supplier contracts, reducing overtime through better planning, or cutting rework costs by improving quality.

Agility

If efficiency is about running fast, Agility is about being quick to change direction. Why is agility so crucial? Because in manufacturing, change is the only constant: markets shift, supply chains break, customization is increasing, and product life cycles are shortening. An agile manufacturer can handle these twists and turns gracefully, whereas a rigid one cracks under pressure. An agile manufacturing organization can scale up or down quickly, switch product mix on the fly, and recover from surprises (like supply chain disruptions or sudden spikes in demand) faster than competitors. The COVID-19 pandemic was the ultimate test of agility for many manufacturers, separating those who could adapt overnight from those who struggled for months. Here are the key subcomponents of Agility:

Flexible Operations: The ability to reconfigure production lines and workflows quickly. This could mean modular equipment that can be adjusted to make different products, quick changeover techniques (SMED – Single-Minute Exchange of Dies – in lean lingo), or multi-skilled teams that can be reassigned as needed. Flexible operations make a factory more like a gymnast than a rigid statue. For example, a flexible auto factory might switch from producing sedans to SUVs in the same facility based on demand, or even pivot to make ventilators in an emergency. During the pandemic, some distilleries famously switched to producing hand sanitizer. Now that’s flexibility! In less extreme cases, it could be as simple as rearranging shifts or equipment to accommodate a rush order.

Adaptable Workflows: This is about process adaptability: having workflows (and an organizational mindset) that embrace change. Instead of clinging to “how we’ve always done it,” adaptable workflows leverage real-time information and empowerment to alter procedures when needed. For instance, if a quality issue arises, an adaptable workflow might reroute products for re-inspection or adjust a process parameter immediately, rather than waiting for a slow approval chain. Culturally, it’s teaching teams to respond to daily conditions, if one machine is down, workers can move to another task; if a shipment is delayed, adjust the production sequence. It’s agility at the micro (workflow) level supporting agility at the macro level.

Dynamic Resource Allocation: This subcomponent is about rapidly reallocating resources (people, machines, inventory, logistics, etc.) to where they’re needed most in the moment. It’s like real-time balancing. If demand for Product A spikes this week, dynamic allocation might pull in extra staff for that line, run an extra shift, or divert raw materials from Product B (which is temporarily slow-selling).

Aspirational Needs: Seeing the Future and Shaping It

At the peak of the pyramid are the Aspirational Needs, the level where manufacturers stop worrying about survival and start defining what comes next. But aspiration isn’t just about big bets or shiny tech. It starts with predictability, the ability to see what’s ahead with confidence. Accurate forecasts, resilient supply chains, and a culture of risk awareness make it possible to plan boldly without tripping over surprises. Predictability is the anchor that keeps ambition grounded.

Once that foresight is secure, the path opens to innovation and growth. This is where a manufacturer reinvents itself, not just improving processes, but creating new products, services, and even business models that reset the competitive playing field. Predictability without innovation leaves you steady but stagnant. Innovation without predictability leaves you bold but brittle. Together, they create the ultimate advantage: the ability to grow, adapt, and lead while others scramble to keep up.

This is the summit. Not where factories simply run well, but where they become the companies others measure against. A place reserved for those who master both the art of seeing clearly and the courage of building boldly.

Predictability

If agility is reacting quickly to change, Predictability is about foreseeing and managing change before it happens, or at least making outcomes more certain. Predictability in manufacturing means you can anticipate demand, plan your operations, and manage risks such that surprises are minimized. It’s the difference between being proactively prepared versus constantly reacting. High predictability is almost like having a crystal ball for your supply chain and production, powered by data and good planning processes (like Sales & Operations Planning, forecasting, risk management). Key subcomponents of Predictability include:

Accurate Forecasts: This is about demand planning and forecasting both sales and production needs accurately. The better your forecasts, the less you overproduce or underproduce, and the smoother your operations. Achieving accurate forecasts is hard (no one has a perfect crystal ball), but with advanced analytics, AI, and demand sensing, companies are making strides. In manufacturing, accurate forecasts allow you to schedule production efficiently and ensure materials are in place. It’s aligning production closely with actual market needs, which prevents the classic whipsaw of too much stock then too little.

Resilient Networks: Even with good forecasts, stuff happens. Ports get shut down, suppliers fail, natural disasters strike. A resilient supply network means you have built-in redundancy and flexibility: multiple suppliers for key materials (dual sourcing), alternative shipping routes, maybe regionalized production. It’s designing the supply chain to withstand shocks. R. The idea is to avoid single points of failure and ensure that when the unexpected occurs, you can still keep the factory running (or at least recover quickly).

Risk Awareness: This is the cultural and procedural side of predictability, constantly identifying and managing risks. It means having risk registers, scenario planning (“What do we do if supplier X’s plant goes down or if demand drops 20% next quarter?”), and involving leadership in these conversations. It’s very much a “plan for the worst, hope for the best” mentality. Organizations that do this well often have cross-functional risk teams and use tools like Failure Mode Effects Analysis (FMEA) or digital twins to simulate and prepare for disruptions.

Innovation & Growth

This represents the ultimate goals of many manufacturing leaders: to innovate – in products, processes, even business models, and to drive growth that cements the company’s position as an industry leader. It’s about creating new value and unlocking future opportunities beyond the current grind. Subcomponents include:

Business Model Renewal: This refers to the ability to reinvent how you create and capture value. It could mean adopting new business models like servitization (e.g., selling your machine output as a service instead of just selling machines), embracing digital platforms, or targeting new markets. Business model renewal is what keeps even old companies young at heart. A classic example is how Netflix moved from mailing DVDs to streaming, a complete business model overhaul that made them a leader. In manufacturing, think of a traditional equipment manufacturer like John Deere adding digital services and predictive analytics to its tractors, or Rolls-Royce shifting to “Power by the Hour” (charging airlines per hour of engine operation rather than selling engines outright). Those are business model innovations. Another form is embracing Industry 4.0 to offer new value: for instance, a factory might open a new revenue stream by using its excess manufacturing data to advise other companies (consulting/services), or by producing customized products on-demand instead of mass production. The key is a willingness to pivot and try new ways of delivering value. Companies that do this avoid the fate of once-dominant players who stagnated (e.g., Kodak sticking to film too long, or Blockbuster ignoring streaming).

Industry Leadership: This is the aspirational goal of being at the forefront of your industry – known for excellence, innovation, and setting the trends. It’s achieved by continuously improving and innovating in both products and processes. An industry leader is often the one with the best quality, or the most advanced technology, or the boldest strategies that others later copy. Toyota became an industry leader through its manufacturing excellence (everyone copied lean). Amazon set new standards in supply chain speed and agility that forced entire retail and logistics industries to step up. Tesla pushed the auto industry toward electric vehicles and over-the-air updates, dragging even legacy giants into a new era. For a more traditional manufacturing example, Siemens has positioned itself as a leader in digitalizing manufacturing – investing heavily in automation, software, and even evolving its business to help other manufacturers digitize (a growth avenue). Industry leadership often means you’re the benchmark others measure against. Achieving this position usually requires consistent innovation and a culture that never settles for “good enough.” It’s the epitome of that kaizen mindset – always reaching for the next improvement or breakthrough.

Bringing It All Together

Just like a Maslow pyramid, the Hierarchy of Manufacturing Needs reminds us that you can’t skip steps. A fancy digital initiative or ambitious innovation project will crumble if foundational safety or reliability needs aren’t met. Conversely, a shop floor that’s safe, stable, efficient, and agile creates the perfect launchpad for innovation and growth.

References:

Huntington, C. (n.d.). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: Definition, examples & explanation. The Berkeley Well-Being Institute. Retrieved September 26, 2025, from https://www.berkeleywellbeing.com/maslows-hierarchy-of-needs.html