When Code Becomes the Culprit

This year I had the opportunity to serve as a contributing analyst and editor for Copia Automation’s 2nd Annual State of Industrial DevOps Report. Being close to the process reviewing the data, testing interpretations, and challenging the framing—gave me a deeper appreciation for the findings than simply reading the final report could.

One statistic stood out above all: 45% of all manufacturing downtime is attributed to industrial code. In other words, nearly half of the disruptions in production are not rooted in equipment wear, supply shortages, or operator error, but in the logic that runs the machines.

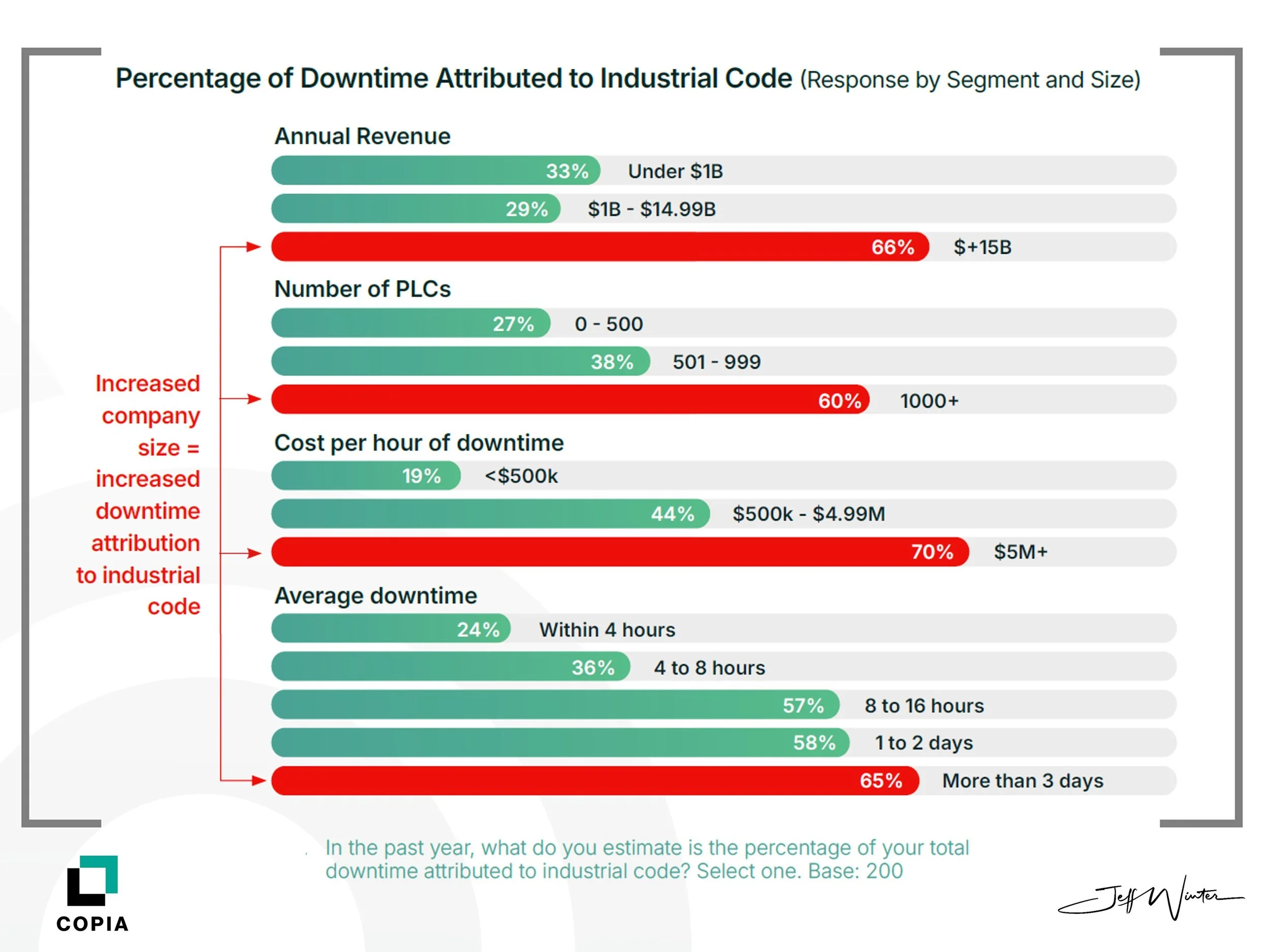

The data also revealed a direct correlation between company size and the share of downtime tied to code. Smaller manufacturers (under $1B in revenue) attributed 33% of downtime to industrial code. Mid-sized companies ($1B–$14.9B) put the number closer to 29%. But among the largest enterprises ($15B+), the figure jumps to 66%.

That scale effect cannot be ignored. Complexity grows with size, and with it comes a higher probability that downtime stems from the software that orchestrates operations.

Downtime in Financial Terms

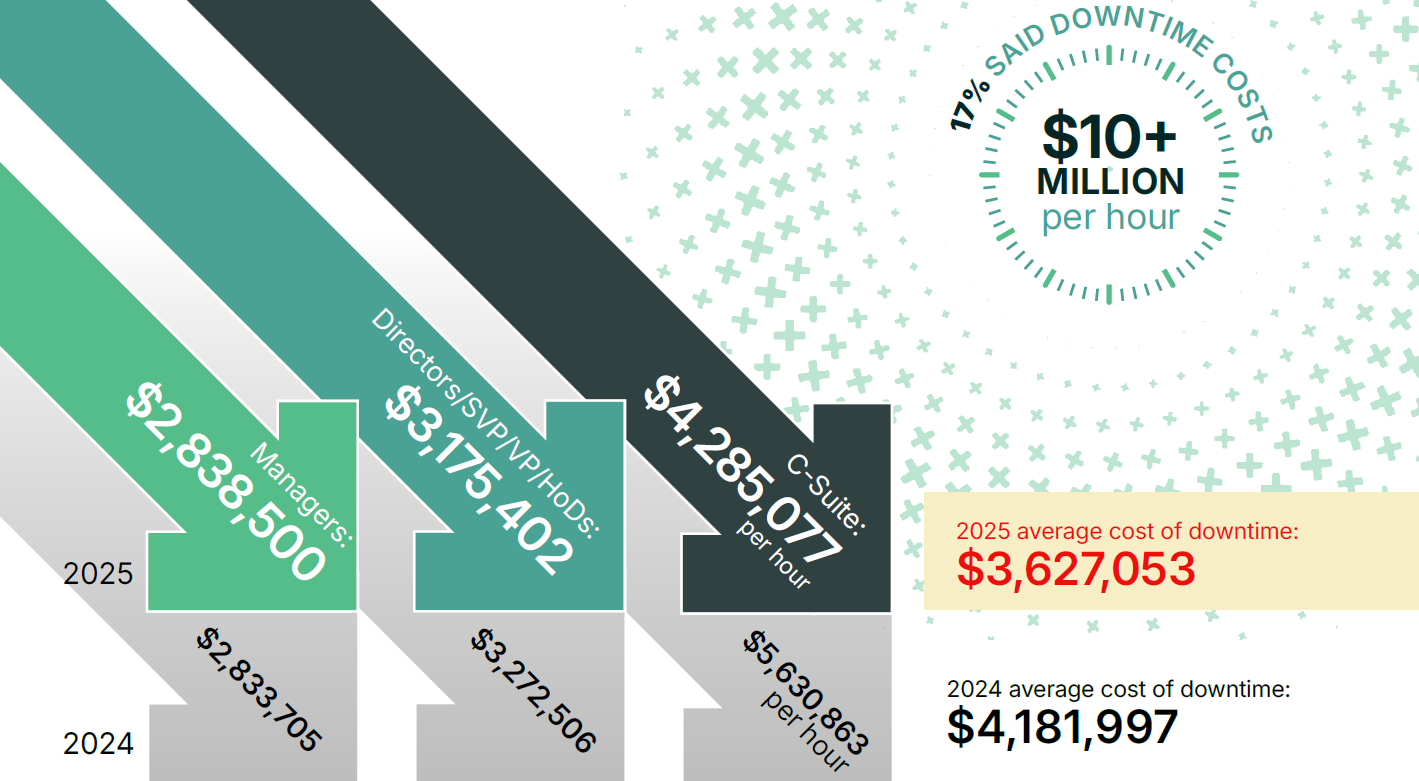

The cost of downtime has always been a difficult figure to pin down, but the report makes clear just how significant the stakes are. Across all respondents, the average reported cost of downtime is $3.6 million per hour, with C-Suite executives estimating even higher at $4.29 million.

If nearly half of that cost is driven by code-related issues, the financial exposure is immense. For large enterprises attributing two-thirds of stoppages to code, the impact is even more pronounced. At that scale, each code failure represents millions of dollars in lost production, missed shipments, wasted labor, and cascading disruptions throughout the value chain.

Complexity as the Driver

The deeper story here is not simply that code is problematic, but that complexity is the real accelerant. Large organizations often manage more than 2,000 PLCs and over 2,100 connected devices such as sensors, cameras, and drives. On average, they run code across six different PLC vendors, each with its own ecosystem.

This ecosystem is fragile by design. Every undocumented change, every outdated backup, every inconsistent versioning practice adds another layer of risk. When issues arise, recovery is not quick: the report found that the average time to resolve a code-related downtime event is 28 hours. That is not a minor delay—it is the disruption of an entire production week.

Large enterprises in particular reported higher average durations, with 65% saying their downtime lasted more than three days, and higher cost-per-hour figures, with 70% citing over $5 million per hour. This suggests that size does not provide resilience. Instead, it compounds fragility.

Diverging Perspectives

The report also highlights an important gap in perception. C-Suite leaders estimated that 52% of downtime comes from code, while managers attributed only 30%.

This divergence is not just a matter of perspective; it reflects structural misalignment. Executives recognize that systemic issues—industrial code, cybersecurity, integration—pose the greatest risks to enterprise performance. Managers, focused on immediate floor-level challenges, tend to emphasize hardware failures or human error.

When these viewpoints diverge, organizations risk underinvesting in long-term resilience. Quick fixes on the plant floor address immediate symptoms, but without systemic visibility and control, they allow technical debt to accumulate until the next failure occurs.

Moving Beyond Quick Fixes

One of the most concerning findings was how prevalent ad hoc code fixes remain. Over 80% of respondents said these “band-aid” solutions are common. While they restore production in the moment, they also embed fragility into systems. The long recovery times reported elsewhere in the survey suggest that these quick fixes may actually extend downtime over the long term.

This reflects a cultural challenge as much as a technical one. Organizations reward speed of recovery but rarely measure quality of recovery. In practice, this means teams are incentivized to get lines running again quickly, even if the underlying problem remains unresolved.

For decades, manufacturers have invested heavily in frameworks to manage physical assets: predictive maintenance, condition monitoring, spare parts optimization. These approaches made sense when the primary sources of failure were mechanical.

But when nearly half of downtime is tied to industrial code, new approaches are required. Industrial code needs to be managed with the same discipline as IT software: version control, automated backups, systematic testing, and continuous monitoring.

There are two key steps that leaders should take:

Establish industrial code lifecycle management (ICLM) as a core discipline. This means automating version control and backups, standardizing change management, and ensuring every code change is visible across the enterprise.

Unify fragmented tools into a single platform. The report found that the average facility uses 13 different software packages to manage operations. This fragmentation creates confusion and delays. A unified approach reduces errors and provides the visibility required for faster, more reliable recovery.

Why This Matters

In my view, this data is not simply about downtime. It is about recognizing that manufacturing has become a software-driven industry. Machines remain critical, but the true leverage, and the true risk, resides in the logic that directs them.

Unlike physical assets, software is dynamic. It changes frequently, it can be altered invisibly, and it accumulates debt rapidly. This makes it simultaneously more powerful and more fragile than machines. Leaders who fail to adapt to this reality will continue to fight the wrong battles, investing in mechanical resilience while software fragility silently grows.

Industrial DevOps is one answer to this problem. By embedding practices like automated backups, version control, and integrated cybersecurity into operations, manufacturers can treat code as a first-class operational asset rather than an afterthought. This is not just about reducing downtime; it is about creating the conditions for resilience, security, and innovation.

References:

Copia Automation - 2nd Annual State of Industrial DevOps Report, 2025: https://www.copia.io/resources/the-2nd-annual-state-of-industrial-devops-report